Aborigines believe that all beings on Earth are interconnected and form one great system that comes from their great spiritual ancestors in the Dream Time, which is also called the Creation Time. This is the period before any material world comes into existence. The Aborigines, however, believe that it is still possible to get to " Dream Time" throught dreams or appropriate magical rituals. Aborigines, in order to be closer to the "Dream Time", make totems called Czuringa, these are objects made of wood or stone, are flat, oval, sometimes round. These are the things in which the power of the spirits is manifested. Czuringa is precisely the symbol of the "Time of Sleep". The supreme slogan of the Surrealists, who based their movement precisely on dreaming: "Cahnger la vie" (Change your life), also included the revolution of objects. In the first manifesto, Breton spoke of a spiritual connection with things that gave him "poetic awareness" by repeating a spiritual connection with them a thousand times. The transformed equipment was considered by the surrealists as "liberators of desire", engines of imagination, tools to fight common sense, a projection of a total poetic attitude. Agnieszka Taborska in her book about surrealists “Conspirators of the Imagination”, explains their fascination with objects as follows: “Surrealists' interest in things comes from the conviction that the surrealism is in reality. Surreal objects were heralds of this other reality. They were evidence of the power of imagination, an expression of curiosity with the unlimited number of possible solutions. They released things from the shackles of utility imposed on them. They evoked anxiety in the viewer and expressed the inexpressible. They can be compared to automatic writing: here and there the final effect is impossible to predict”. For surrealists, meeting a found object - on a beach, at a flea market, in a forest - meant its transformation. The object became a habitat of hidden content, it began to play a role analogous to a dream. Aboriginal totems and rituals connected them with the "Dream Time", finds, as well as Surrealists rituals, which include drifting, wandering around the city, drawing and automatic writing, had the same goal - touching this thin border of sleep and waking, reversing the order and reality.

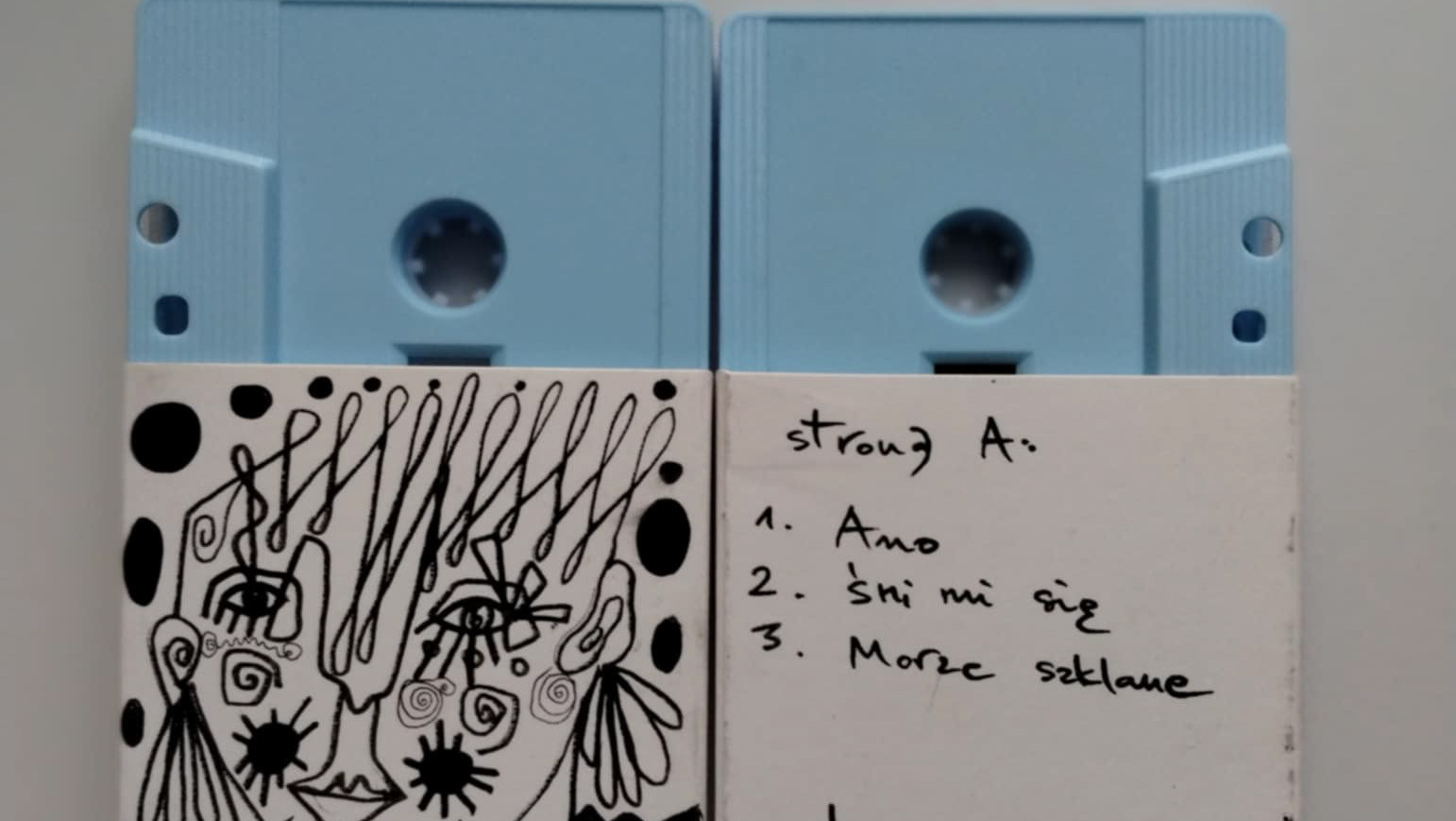

The Magic Noise project performs a function of research laboratory for the relationship between sound, dream and an object that becomes a dream itself. This project is for me a punk attempt to transfer to the mythical "Dream Time". I make my first steps, collecting magical artifacts, more or less peculiar objects from the places where I resident, transforming them at the same time and saving them in the form of sound cards.

Aborygeni wierzą, że wszystkie istoty na Ziemi są ze sobą powiązane i tworzą jeden wielki system, który pochodzi od ich wielkich duchowych przodków z Czasu Snu, który jest również nazywany Czasem Tworzenia. Jest to okres przed powstaniem jakiegokolwiek świata materialnego. Aborygeni uważają jednak, że nadal można się dostać do „Czasu Snu” za pomocą marzeń sennych lub odpowiednich rytuałów magicznych.

Aborygeni, by być bliżej „Czasu snu”, między innymi wykonują totemy o nazwie Czuringa, są to przedmioty z drewna lub kamienia, płaskie, owalne, czasem okrągłe. Są to rzeczy w których manifestuje się moc duchów. Czuringa jest właśnie symbolem „Czasu Snu”.

Naczelne hasło Surrealistów, którzy swój ruch opierali właśnie na śnieniu : „Cahnger la vie” (Zmień życie) obejmowało także rewolucję przedmiotów. W pierwszym manifeście Breton mówił o duchowym związku z rzeczami, dzięki któremu zyskał „poetycką świadomość”, poprzez tysiąckrotnie powtarzanie nawiązywania duchowej z nimi łączności. Przekształcone sprzęty surrealiści uważali za „wyzwolicieli pragnienia”, motory wyobraźni, narzędzia walki ze zdrowym rozsądkiem, projekcję totalnej postawy poetyckiej.

Agnieszka Taborska w kultowej książce o surrealistach „Spiskowcy wyobraźni” tłumaczy ich fascynację przedmiotami w ten sposób: „Zainteresowanie surrealistów rzeczami wzięło się z przekonania, że nadrzeczywistość tkwi w rzeczywistości. Surrealistyczne przedmioty były owej innej rzeczywistości zwiastunami. Stanowiły dowód na moc wyobraźni, wyraz ciekawości nieograniczoną ilością rozwiązań możliwych. Wyzwalały rzeczy z pęt narzuconej im użytkowości. Wywoływały w widzu niepokój, wyrażały niewyrażalne. Porównać je można do pisma automatycznego: i tu i tam ostatecznego efektu nie sposób przewidzieć” .

Dla surrealistów spotkanie z przedmiotem znalezionym – na plaży, na pchlim targu, w lesie – oznaczało jego przemianę. Przedmiot stawał się siedliskiem ukrytych treści, zaczynał odgrywać rolę analogiczną do marzenia sennego.

Totemy i obrzędy Aborygenów łączyły ich z „Czasem Snów”, znaleziska, a także rytuały Surrealistów do których możemy między innymi zaliczyć dryfowanie, błądzenie po mieście, rysowanie i pisanie automatyczne, miało ten sam cel – dotknięcie tej cienkiej granicy snu i jawy, odwrócenie porządków i rzeczywistości.

Projekt Magic Noise pełni dla mnie funkcję laboratorium relacji dźwięku, snu i przedmiotu, który sam w sobie staje się marzeniem sennym,. Jest dla mnie punkową próbą przeniesienia się do mitycznego „Czasu Snu” w który wierzą Aborygeni. Podejmuję pierwsze próby, zbierając z miejsc w których się znajduję magiczne artefakty, mniej lub bardziej osobliwe przedmioty i dźwięki, transformując je tym samym w sny, performując lub zapisując w formie pocztówek dźwiękowych.